Burn the Witch: J.K. Rowling and I

On witch hunts, spiritual interventions, and the betrayal of a hero.

“Do you renounce the devil and all of his works and ways?” the priest asked my godparents at my baptism in the belly of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, thirty years ago, in Forest Hills, Queens.

“Noooooo!!!!” was my answering wail.

I was two years old, soaked with sweat and tears, wisps of downy brown hair plastered to my head. The front of my pretty white dress was marred with stripes of yellow from a highlighter my grandmother had given me in the car on the ride over to the church. I was truly a sight to behold, shrieking and wailing as I was asked to reject evil and be sealed into the body of Christ. After that display at my baptism, my family began (affectionately) referring to me as the Devil Child.

The story of my baptism has become a family favorite. It’s a funny little tale used to entertain, to illustrate my odd and mercurial nature as a small child, or else a cautionary tale that illustrates why you should baptize infants, and not toddlers. As I’ve grown older, however, that story always makes me wonder how my behaviors growing up might have been perceived had I been born in an earlier century, or even just a handful of decades before. People have been accused of witchcraft for less.

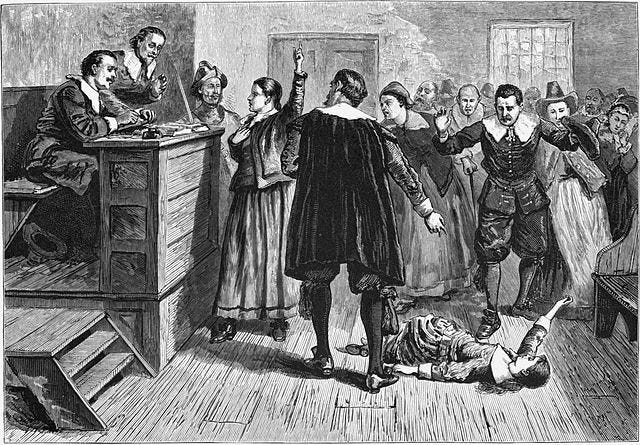

As an odd, magical little thing who grew up in the Northeast, I had the obligatory obsession with the Salem Witch Trials. I was fascinated with the kind of thinking that led to such widespread hysteria and what strange times that had led neighbors to turn on neighbors. I was curious about what it was like to live in fear of forces beyond your ordered understanding of the world. I’ll admit- I wanted the magic to be real even if it was dangerous.

I grew up religious, a fact that surprises some and connects dots for others. My church was, by and large, a welcoming and loving environment. I was never asked to witness to people, or to “save” anyone, and all the messaging I received was about love and community, but also acceptance. To me, church was mostly about coloring, learning hymns, and the buttered rolls at the coffee hour after the service.

As many children do, I loved fairytales, and stories of witches and wizards. Anyone who’s known me for any stretch of time will know the rabid way in which I read the Harry Potter books, and how easily I could be consumed by stories of castles and enchanted forests, fantastic creatures, by magic and mystery. No one at our church seemed to mind, and I was content to play Fairies and Dragons in the empty sanctuary with my brother and our friend Tori, the three of us using our mothers’ scarves as cloaks and pretending to cast spells on each other.

As I grew up in our church, I was always given the space to disagree or argue, and no one told me I would go to hell for it. That is, until I was eleven, and went away to a sleepaway Christian camp in the Adirondacks.

It's important, now, to think about how witch hunts begin. Those targeted are often the weakest members of society, those that do not fit the norm, that do not conform exactly to the social hierarchy of a given group. But what makes them targets in the first place? What’s the spark that leads people to turn on others and start the wheel of hysteria turning? It is often at periods of economic insecurity and swift social change, when people begin to fear for their way of life changing, their choices being called into question for perhaps the first time.

the author at the Wizarding World of Harry Potter, age 19

My magical tendencies were accepted at my church, the adults around me content to see me lugging my dog-eared copy of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban with me wherever I went, so I was surprised to find that Camp Tapawingo was… quite different from what I had come to expect from church. As eleven-year-olds are wont to do, I had written “I Love Harry Potter” on my jeans in colorful fabric markers, along with lightning bolts, hearts, and stars. When I returned to my cabin one evening, I found my whole cabin gathered there, along with our two counselors. They wanted to talk to me about the dangers of Witchcraft, and their concern for my immortal soul.

I don’t remember much about the content of the intervention. I remember trying to assure them that Harry Potter wasn’t evil. None of them had read it, filled as they assumed it was with immorality and recipes for boiling babies and I tried in vain to convince them that its message was about love and acceptance, and that it was consistent with Jesus’ teachings. I remember one of the girls, whose parents had been missionaries in Africa (I don’t think she ever even mentioned what country, just “Africa”), telling us about how the villagers had tried to give her parents copies of Harry Potter as gifts for their children, and how her parents knew that more work needed to be done to “save” them. That same girl told me she believed her own personal mission that week was to “save” me too. I didn’t realize that I needed saving. I thought just being a good person, a good Christian, was enough. As it turns out, it was not. If I didn’t reject evil, if I didn’t accept Jesus Christ into my heart as my Lord and Savior (no one was ever really clear on how this process worked, and how they could tell if I hadn’t), then I would spend all of eternity in the black nothingness of Hell, while good Christians would be rewarded in the Kingdom of Heaven.

Up until that point in time, I had thought I was a good person, or at least that I tried really really hard to be. I treated others with kindness and gentleness. I was active in my church and sang with the children’s choir. I did community service projects with my youth group; I prayed every night before bed. Before going to camp, I had thought that Harry Potter fit into my understanding of the world. It mirrored the morality taught to me by my parents, by the Bible (the bits I had read), and by the congregation of Gilead Presbyterian Church. After camp, I was plagued by nightmares, by the fear that because I was unwilling to die for Christ, that I would not be welcomed into Heaven. I also feared, for the first time, that magic was real. I was eleven, after all, and I still half-believed that I would be receiving my Hogwarts letter that summer. I still hoped that I could be whisked off to a magical world where I had power, had friends, had a place where I fit in. It was not at school, and it certainly was not at camp.

While I never received my Hogwarts letter, those books did take me to another world. My life would look very different were it not for Harry Potter. My best friend began our friendship with the words “So, I hear you like Harry Potter” in our 7th grade Homeroom. I’ve made dozens of friends and had countless experiences that would not have been possible without J.K. Rowling’s books. I was on the Quidditch team in college, I’ve been to dozens of Wrock (Wizard Rock) shows- I was in a Harry Potter fan film, for Merlin’s sake! I stayed loyal to the stories I loved, even when I was told they would damn me to Hell. And then, the author of my beloved books liked a few transphobic tweets.

That’s how it started, mind. A spark, if left alone to burn out, will not destroy the forest.

In Salem, the witch hunts began when a few teenaged girls began having fits and accused an enslaved woman and two others of being their tormentor; of being in league with the devil. Vulnerable people, with little power, who seek to control those who have even less. We see it all the time, in the voting records of people like senator Susan Collins of Maine, who packages herself as a moderate republican, who pretends to be reasonable, and then votes with her whiteness. We see it in white women who weaponize their tears after being caught on camera being racist in shopping malls or public parks. We see it in J.K. Rowling, who claims loudly that she “loves trans people” but questions whether they exist, whether they should have access to healthcare, whether they should be able to use the bathroom in public. The comments started off small- liking tweets with transphobic dog whistles in them or equating having a uterus to being a woman (the only way to be a woman, in her eyes). Then she published an essay on her blog, in her own words, accusing trans women of being men in disguise, who want to use the women’s bathroom only to assault “real” women. And the worst part? She used her own experience as a domestic abuse survivor to justify her demonizing of a part of the LGBT community.

When I read J.K. Rowling’s essay, I was horrified. The author I had looked up to for so long, who had shaped so much of my morality, who wrote the line “it matters not what someone is born, but what they grow to be” could be so… hateful. And worse, that she could use her trauma to scapegoat a vulnerable community. Suddenly all her words twisted around and in on themselves, and returning to the world she created felt like a lance to the heart instead of a soothing balm. How could the woman who helped to teach me that the hero was the one who stood up to hatred, who led with love and compassion for those the world neglects, how could she be the one leading a witch hunt, then turning around and claiming she’s the victim? Reading “The Crucible” in high school should have prepared me for this.

Even after the intense feeling of alienation and re-thinking of my relationship to my faith that occurred after camp when I was eleven, I still maintained a personal relationship to God. I had to re-order my thoughts on organized religion, and I had to cobble together my own way to practice my faith, but somewhere, still, I believed there was a higher power, and that They had a plan. I’m a storyteller by nature, and I needed to know that there’s a narrative, a shining golden thread that ties together the disparate parts of my life. I needed to know that there was a reason for my pain, that each trauma somehow happened for a reason, even if I was never to know what it is. Through that belief, I was able to make sense of my depression and anxiety. I was able to make sense of my sexual assault in college this way as well, reasoning that because I went through it, I could help others around me when they were similarly hurt. I made sense of countless little hurts this way. I didn’t want to be a collection of senseless traumas, a broken girl with no path- I wanted to be the heroine experiencing her trials until she found her place in a vast pantheon of brave heroes. Instead, I wondered if I was doomed from the start, a dark and wrong girl, destined only for darkness.

Then, a few people around me started to read the J.K. Rowling essay, and they read the defenses of her without further investigating what she had said, her consistent harm. They started to weaponize my assault as well, claiming I needed protection from men who might want to follow me into a bathroom under the guise of being transgender. I felt horror and revulsion, but I also felt paralyzed, like my brain was somehow being unplugged, and I was unable to form a coherent counterargument. Here is the thing; Joanne Rowling is persuasive. Her books, her essay, her social media presence all present an ordered view of the world, with black and white morality, with right and wrong, with heroes and villains. It’s comforting, in a way, to find boogeymen hiding under the bed, and it’s much easier to believe you will be hurt by an evil consortium of rapists pretending to be trans rather than a boyfriend, a family member, a classmate. It’s easier to be afraid of evil strangers, rather than believe the people close to you are capable of hurting you. But that doesn’t make it right.

In her book “Monsters”, Claire Dederer writes about Harry Potter, saying “The reader is left with a sensation of an ordained universe, a place where things make sense if you just pay attention. It’s easy to see how this would be appealing for young readers- especially for YA readers, people who might be starting to feel that the world doesn't make sense at all.” Is that not what I was looking for in my faith? Books like Harry Potter helped to reaffirm these beliefs, and the truth in an ordered world, where good and evil could be clearly spotted, identified, and fought. Real evil doesn’t work like that.

Recently, celebrity couple Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis have come under fire for writing letters of support for their friend and convicted rapist Danny Masterson. In the letters, they describe Masterson as a good friend, a good father, and an “older brother figure”. They write about times in which he defended women or was kind to strangers. The internet erupted in anger, feeling a deep sense of betrayal that someone who fronts an anti-sex-trafficking organization could publicly defend a rapist. The world is not black and white, and morality and justice are complicated. People can do horrible things and still be nice to their friends. They can cause unimaginable harm and still be good fathers. We are asked to overlook horrors because the people who commit them don’t “seem” like monsters.

Witch hunts begin by othering. They begin when we attempt to separate those whose lives and beliefs don’t fit our own. In recent years, we hear the term “witch hunt” most commonly used to describe an internet mob harassing a single, highly visible person. It’s a term former President Trump likes to throw around, as well as people like Elon Musk, and Ms. Rowling. And though witch hunts may have started in a place with just one or two individuals being accused, it was never an isolated incident. Historically, witch hunts were never “this person said something I dislike so I will run them out of town”. Witch hunts were an environment of fear, that claimed the lives of thousands of people across centuries and all over the world. A fear of the “other” is always dangerous. Now what does that sound more like; a group of activists telling people not to give more money to a multi-millionaire, or a very well-placed public figure throwing fear and suspicion onto a vulnerable group?

I’m going to be frank- writing this essay has been especially difficult. I’ve been writing it for over two months now, constantly re-arranging my thoughts, seeking more and more sources, hoping someone- anyone- can say what I want to say so that I won’t have to. I have had to reorder my entire relationship to my worldview in the past five years, since I had my last real break with my faith. I knew my feelings about my former idol would be complicated, that detangling those feelings would be tricky, but before I began, I didn’t realize how deeply tied to my identity her work was, or that it had any relationship to my break from Christianity as an adult. It seems naïve, now. In school I was taunted by kids calling me “Harry Potter Girl”, but somehow, I still thought I could keep it all separate. I could be an adult, putting aside childish things and leaving the magic behind. I could learn that the world is an inherently random place, that so-called “evil” can live in “good” people, people you love. I could, I could. I have not wanted to. To borrow a phrase from The X-Files, I want to believe.

I am not trans, so I cannot speak for that community, nor am I an expert on trans activism, healthcare, or legislation in either Britain or the U.S., so I’ve tried to gather resources from those who can speak more concisely on the subject. If you’re unfamiliar with what J.K. Rowling has said and done with regards to her views on the trans community, you can read about that here. If you’d like more information on the lived experience of trans youth, Daniel Radcliffe worked with the Trevor Project recently to create a thoughtful interview series. If you’re curious about trans healthcare and legislation in the U.S., Last Week Tonight has done a few really well-done segments on the subject.

If you have the time, I’d also recommend this video essay by ContraPoints on Youtube. It’s long, but she covers a lot of ground, discussing homophobia, transphobia, “witch hunts”, and the conversation surrounding rational debate and the best way to change people's minds when it comes to bigotry.